Dimitri Venkov: “One needs to film what can’t be seen in real life or in other films”

Dimitri Venkov’s solo exhibition at Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA), which opens in autumn 2019, will feature well-known works and the premiere of a new film about a game, created with support from Gazprombank.

Dimitri Venkov is one of the most brilliant representatives of the Russian art scene working in the field of video art. His films are highly rated by the professional community, not only in Russia but across Europe. In 2012, he was awarded the Kandinsky Prize as young artist of the year for the film Mad Imitators. In 2018 he received a prize at the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival in Germany for the film The Hymns of Muscovy, which is now part of the Gazprombank collection.

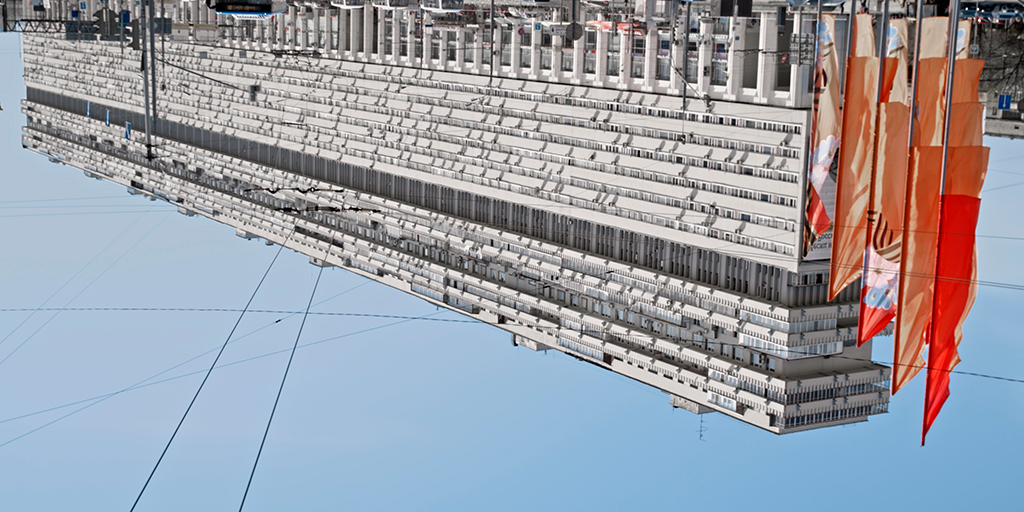

Shooting of the video "The Shining Will Come Crashing Down". Photo: Maxim Zmeev

Your film Mad Imitators, the earliest work to be shown at your exhibition at Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp, was considered to be a parody aimed at the art world. It tells the story of a marginal tribe of contemporary savages living by the Moscow Ring Road, whose wishes come true with the help of magical rituals based on imitation. The roles of the "aboriginals" and the "scientists" who researched the group were played by artists, curators and critics.

Did you really intend to poke fun at the art world?

That wasn’t my intention. I was aiming at the anthropological community, at scientists. If anything, I was trying to parody anthropological discourse. At that time, I was very interested in Jean Rouch [the French filmmaker and anthropologist]. The idea that this was a metaphor for the art world came up later. That’s how it was received by the art community.

You mean initially you hadn’t been thinking that way?

I hadn’t. I made a film based on the canons of classic ethnographic cinema. I studied the literature on cargo cults, ecstatic rituals and new religious movements. I devised the habitus of this community, its way of life, and then interpreted it with the help of experts. When I showed the film at anthropological festivals many people thought it was scientific research or visual anthropology.

“Mad imitators”. 2012

Who, anthropologists?

Yes, western anthropologists. In reviews they wrote that you should never deny a voice to the people you film, that it’s a top-down view. For me it was important to show the dichotomy between mad imitators and staid experts. Although at one point they get involved in the overall ecstasy and by the end of the film the experts also fall into a kind of linguistic trance.

Your next film, Krisis, was a court drama set in an imagined space and was also about communities. However, it was inspired by a concrete event in the art community: artist Yuri Albert’s post on Facebook about the dismantling of a Lenin monument in Kiev, which divided opinion between left- and right-leaning commentators.

It was then that I realised that a community could be based on something negative and I began to write a play a little like Sartre’s No Exit, in which I wished to create an image of a community as hell. Whereas Mad Imitators involved meeting "with eyes wide open" the art community with which I had fallen in love and which became my tribe, Krisis was the opposite. It was about disappointment, how "hell is other people". The pendulum swung the other way. Before I met the Moscow art community I had never felt myself to be part of a group, although I implicitly felt the need for this.

You don’t have an art background?

I graduated from the Rodchenko School, and before that I did my masters at the University of Oregon and the International University in Moscow. The academic world didn’t suit me, I’m not a scientist and I couldn’t see myself living that life. Loneliness and isolation is not for me. The art world amazed me with its communality and the horizontal nature of its connections. But then I discovered another, negative side. I tried to look into this problem. It was a personal crisis which I was trying to solve.

“Krisis”. 2016

Did you solve it?

I still have a binary relationship with the art world, but I don’t think that’s a tragedy. The art community is ideal as it helps me to be social, but it also has a negative side.

Maybe it’s because you were initially part of the academic community that you took on the role of researcher-scientist?

I grew up in Novosibirsk, in Akademgorodok. When I began to create works at the Rodchenko School I donned the mask of a pseudoscientist. Then I thought it was a random choice, but later, when I revisited Akademgorodok as an adult, I understood where my interests originated. I didn’t become an academic, but the world of science played a major role in my formation.

You worked on the theme of communities for a time, but in your next film, The Hymns of Muscovy, there are no people at all. Previously you made staged films, but Muscovy is a documentary. Why did your practice take this turn?

I’ve temporarily let go of the theme of communities.

As far as the documentary nature of this work is concerned, the material is not staged but the way it is filmed and the formal side of things are very strict.

Do you associate Moscow with grand style architecture?

At first I wanted to trace the evolution of architectural styles alongside the historical evolution reflected in the various texts of the national anthem. Three architectural epochs — Stalin, Brezhnev and today — match the three versions of the anthem, all of which were written by Sergei Mikhalkov. The first version was written during World War II and focuses on the strength of the Red Army, which will repel the invaders, and the fact that Stalin "inspired us to work and triumph". Then comes the Brezhnev version, from which mention of Stalin disappeared and which was focused on the future: "In the victory of the immortal ideas of communism we see the country to come". The last version includes God, land and ancestors. The "Stalin" version is grand like Stalinist architecture. The "Brezhnev" version is utopian, and at that time architecture was once again focused on functionalism and social utopias. The contemporary version is eclectic, a mix of various past and present styles, and the architecture itself is faceless.

“Hymns of Muscovy”. 2018.

You were awarded a prize for this film at the prestigious Oberhausen International Short Film Festival, and also by FIPRESCI (the International Federation of Film Critics) and e-flux. Did the music play an important role?

An enormous role. The film came together when the music appeared. I told Sasha Manotskov about the film and the fact that I wanted to create a soundtrack based on the melodies of the anthem. At first I wanted to use the words, but he persuaded me not to. I trusted him and it turned out well.

The sky in your film is like the clouds on plafonds in baroque palaces.

I see it as a flight over a blue planet. Architectural constructions float above it like space stations.

Did something change after the festival? Were there new proposals, exhibitions?

I started to get proposals from festivals. Exhibitions are a different subject. The curator of Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp, Nav Haq, invited me to exhibit at M HKA, but it wasn’t connected with the festival. We met at the art forum Alanika in Vladikavkaz in 2015. He invited a number of forum participants to exhibit in the museum’s In Situ space. It’s an interesting space. The fact that it’s triangular gave me the idea for my exhibition. It begins with a wide room, which gradually narrows as the ceiling gets higher. The museum is compact, but there are various different spaces and I simply fell in love.

Are the works in the exhibition arranged according to the principle of reduction?

Yes, that’s exactly what I plan to do. First is Imitators, where there are the most elements. Then Krisis, where there is a single issue which is examined from various angles. Reduction increases with The Hymns of Muscovy, where there is no subject, but there is a discursive foundation. And the next film, which is about volleyball, has no literary basis at all.

Where did the idea for the latest film about a game come from?

I decided that I needed to construct a film as music. Sound and images should be a unified whole. While searching for a way to bring this idea to life I listened to a particular kind of music, especially that by Bernard Parmegiani. The main effect in the film is of changes to the speed with which time passes, from high-speed to extra slow, virtually stopping. Sasha Manotskov suggested I structure the montage based on a phrase from Mozart’s overture for The Marriage of Figaro, which lowers not gradually but in three movements.

How did the female volleyball players react to being filmed?

I think they liked it. Together with my stylist Sveta Hollis, we designed colourful looks which were realistic and suitable for volleyball. They looked like really stylish volleyball players, superstars at the world championships. Camera operator Pasha Filkov created fantastic light. Volleyball is very difficult to film, especially the way we did it. We filmed from all kinds of unusual angles and placed cameras on the court.

Is there victory, a culmination?

There are all of the elements of volleyball. The action develops from fast to slow. It turned out that when slowed down, something other than the game comes to the forefront. The girls’ hands form almost religious gestures, they look at the ball as if it is grace descending from heaven.

Are these gestures not staged?

No, it happens as a result of zooming in on time, which brings up unusual things. At certain speeds the game looks like a religious painting.

Was this the concept from the start?

I created the conditions for the experiment, but I didn’t know exactly what the result would be. I wanted to see what would appear when the material was radically slowed down. Even during filming I could see that other worlds were opening up that were invisible during standard filming or without careful observation, including religious iconography.

One of the features of volleyball is collective action. Was this not of interest to you, given that it’s also a sign of a community?

Here I wasn’t thinking about the collective. I was working with movement, rhythm and music.

In other words, you moved from narrative and stories to purely formal categories?

When making my first films I thought the main thing was the story. Initially, I wanted to make cinematic films and my first works involved a focus on structure more than form. I gradually came to understand something very simple, that video is primarily a visual medium and in order to do something new one needs to film something that can’t be seen in real life or in other films.

Have you thought about becoming a film director?

Sometimes I think that sooner or later I’ll make a full-length film, but at the moment something is pointing me in a different direction, towards the reduction of narrative and formal experiments. But if I get the urge to make a full-length film and have the opportunity, why not?